Although immunotherapy has been revolutionary in the world of cancer treatments, not everyone responds well to it. Unfortunately, if a patient doesn’t respond well to an immunotherapy treatment, precious time can be lost.

Currently, the only way to test whether a patient will respond well to immunotherapy without subjecting them to the immunotherapy itself – a try-and-see approach – is to do an immunohistochemistry analysis. But this method involves a biopsy of the tumour, making it invasive for the patient. As well as that, it only provides a snapshot of a small part of the tumour, which doesn’t give a full picture of what is happening, and it can usually only be done once, since it is so invasive. In some cases, it’s not feasible to do a biopsy because of the location of the tumour, so an alternative method is badly needed.

The IMI Immune-Image project investigated a new, non-invasive way to test whether a patient will respond well to a particular immunotherapy, using imaging techniques. The new method gives a whole-body overview, as well as being far less invasive for patients since no biopsy is needed. It can also be repeated easily as many times as necessary to track the progression of the tumour and the effectiveness of treatment.

People who don’t respond well to immunotherapy often have particular patterns of immune cells called immunosuppressive tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) inside their bodies. These immune cells can inhibit the effectiveness of an immunotherapy, and they are extremely versatile, take many forms and up until now have proved difficult to spot.

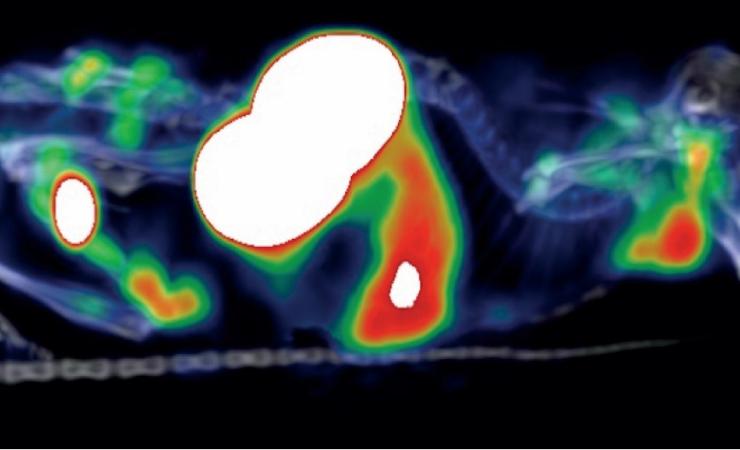

The Immune-Image study successfully developed tiny nanobody immunotracers that attach to certain proteins that are found on the surface of TAMs. The patient undergoes a PET scan, and the attached nanobodies light up due to radioactivity and can be seen on the scan, enabling the clinician to calculate how many TAMs a person has.

By examining the number and distribution of the TAMs, researchers can estimate the chances of a person rejecting an immunotherapy.

“The ultimate grail with this technique is that clinicians will be able to make a conscious decision much earlier [about how to treat their patient]. By looking at what’s happening with the immune system we can already predict that this person will respond well to immunotherapy and this person won’t, and a fast decision can then be made to change the therapy regimen,” says Timo De Groof of Vrije Universiteit Brussel, one of the lead researchers involved in the study. “We can save lives by giving the right treatment to the right patient much more quickly.”

The work reported in the peer-reviewed paper was carried out in mouse studies, but tests are already being run in non-human primates, and De Groof says that human trials will take place as soon as next year.

The public-private partnership structure of the Immune-Image project was especially valuable, as it meant that the study could generate results that are more likely to have a clinical impact.

“Having the perspective of the pharma companies meant that we could see how we could make a clinical impact, not only from an academic point of view but also from an industrial point of view. For the Phase I clinical trial, having their input meant a different perspective on which kinds of patients would be interested and which kinds of therapies are already in the company pipeline that they would be interested in testing,” says De Groof.

The first author on the study on immunotracers was PhD student Yoline Lauwers, whose PhD was also supported by the Immune-Image project. De Groof says that a lot has been achieved, but there is still a long way to go.

“The publication is just the start, we are going to test the tracer in different disease models, not only cancer,” says De Groof. “This tracer is only one of the tracers being investigated in the Immune-Image project but there are others that have promise, and another one is going into clinical trials next year. There is an optimistic future for immune-based imaging.”

Immune-Image is supported by the Innovative Medicines Initiative, a partnership between the European Union and the European pharmaceutical industry.